For an introduction to what goes on in this column, click here.

For an introduction to what goes on in this column, click here.

For the previous installment (Week Two) of the knit-along, click here.

Here we are in Week Four, the final week of our Nineteenth Century Knit-Along. We need to cap our project with its final edging.

Before that, though, let me tell you some more about what you’ve been working on.

The designer of the piece is Jane Gaugain, one of the most important figures in the history of knitting. She has often been called, and with reason, the mother of fiber arts publishing. Okay, I’ve called her that a lot.

Here’s why.

Jane Gaugain (born Jane Alison, in the early 19th century) was a Scotswoman who was born into a tailoring family and married an Edinburgh haberdasher.

After her marriage, she went to work in the family firm, and was instrumental in turning it into a thriving operation. Among the lines sold from the Gaugains’ premises were needlework supplies, including fine, gorgeously dyed merino yarns from Germany that became known in the English speaking world as “Berlin wools.”

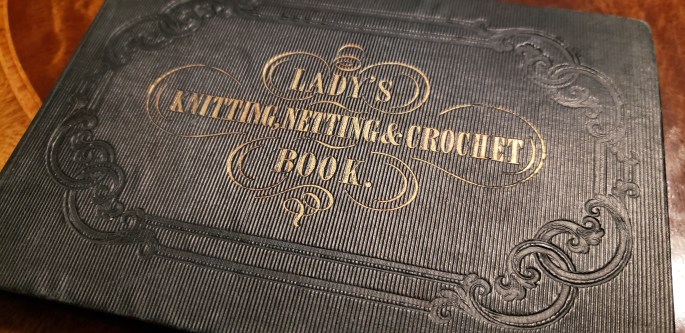

Jane realized that to sell more wool yarns, she needed to provide her customers with knitting patterns–and so in the 1830s she began to distribute them. A subscription volume (a sort of forerunner of the Kickstarter) of mixed patterns in the late 1830s proved so popular that in 1840 she published an expanded version of it entitled, The Lady’s Assistant in Knitting, Netting, and Crochet.

For more about Jane, I highly recommend Kate Davies’ excellent article “In the Steps of Jane Gaugain.”

It’s The Lady’s Assistant from which our pattern was taken, albeit in an adapted form. I was thrilled to tears (no exaggeration–I cried) to find my copy (the later edition of 1846) on a trip to Cambridge, England, in a shop that let it go for a reasonable price because it was outside their specialty.

The original name of the pattern was “Pyrenees Knit Scarf,” and the original differed in several respects from our modern version.

• It was wider. The cast on was 125 stitches.

• It was done in multiple colors. Mrs. Gaugain specifies white and blue.

• It was longer. The suggested length was “about two yards and a half.”

• And it had tassels. The finishing included “drawing up at both ends, and attaching a tassel thereto.”

The pattern called for Berlin wool, but a note at the end suggests “glover’s silk” as an alternative–this being a yarn in a weight similar to that of the Berlin wool, but spun from (did you guess?) silk.

Jane was a pioneer in committing to the printed page what had most often before that been passed along directly from knitter to knitter, by spoken word and demonstration.

Her quick mind and gift for organization are evident from the first. She made handy use of abbreviations (using existing type–so that, for example, a symbol for a knitted decrease could be inverted to indicate the purl version of that decrease). She organized many of her more complex patterns row by row.

And although it certainly could not be said to be charted, there is a hint at charts to come in the way the Pyrenees Scarf pattern is laid out on the page.

Here it is, in full, as printed in my copy.

Finishing Your Scarf

Once you’ve finished the Final Edging, you’ll want to wet block your scarf. Otherwise, no matter how lovely your knitting has been the thing is going to look like a very large and elegantly dyed length of crumpled toilet paper.

Pretty much all knitted lace requires blocking, but lace with patterning on every row requires it especially. I wondered how much of a trial this was going to be. I love the results of blocking lace, but I won’t tell you the process makes me jump for joy.

Here’s what I did, and what I recommend you do.

1. Fill a perfectly clean receptacle (this may be a large bowl, a sink, a washtub, or any such thing) with tepid, clear water. If you like (I like) put in a dollop of a gentle soap like baby shampoo or a purpose made wash like Soak (available from Makers’ Mercantile).

2. Gently swish the soap into the water. You don’t need to make suds. Suds are annoying.

3. Put your scarf gently into the water and press it down below the surface. Let it soak there for at least an hour. Two wouldn’t be amiss.

4. Once the scarf has had a nice bath, remove it from the water. Wet lace will stretch under its own weight, so support it as you lift. Imagine it’s a baby. Or a puppy. Whichever you’d rather hold.

5. Squeeze it gently to remove the excess water. It should be damp, but not sopping.

6. If you haven’t used a no-rinse product like Soak, rinse the piece in a bowl of clear water. Then remove and squeeze, as above. Otherwise, go right to the next step.

7. Now, here’s the beautiful thing. Most lace needs to be pinned out while damp. Jane Gaugain doesn’t specify pinning. In fact, she says nothing about blocking at all. What I found, to my delight, is that the wet Infinito expanded (as superwash wools like to do) under its own weight.

All I did was lay it out flat on a smooth surface, and gently smooth and pat it to the finished dimensions. I used a yardstick to make sure it was square from and even from end to end.

Had I pinned it, it would be a little longer and little wider, and a bit more open. But I was so happy with the un-pinned results that I didn’t bother. I just left it there (in my case, on a little-used kitchen island on a couple of clean towels) until it was mostly dry.

Then of course we needed to use the kitchen island, so while the knitting was still a little damp I draped it over the shower curtain rod in the guest bath.

If you aren’t using Infinito, you may want to pin your piece out. Soak it, lay it out without pins, and see what you think.

Given that we wanted to keep this project within the bounds of one skein, I didn’t elect to gather-and-tassel as prescribed. If you’d like to try that, and/or to try another scarf closer to Mrs. Gaugain’s original vision, I’d love to see what you do.

The Pattern

Enjoy the complete version of the Nineteenth Century Knit-Along scarf pattern by either updating to the latest version on Ravelry HERE, or by downloading the complete pattern via the Makers’ Mercantile website:

Here ends our knit-along. I thank you for coming to play with us. Would you like to do this again? What shall we do next? Post your suggestions in the Ravelry group…

Tools and Materials Appearing in This Issue

Zitron Infinito (100% extra fine merino, 550 yards [500m] per 100g hank), shown in Colorway 2

Soak Wool Wash

About Franklin

Designer, teacher, author and illustrator Franklin Habit is the author of It Itches: A Stash of Knitting Cartoons (Interweave Press, 2008). His newest book, I Dream of Yarn: A Knit and Crochet Coloring Book was brought out by Soho Publishing in May 2016 and is in its second printing.

He travels constantly to teach knitters at shops and guilds across the country and internationally; and has been a popular member of the faculties of such festivals as Vogue Knitting Live!, STITCHES Events, the Maryland Sheep and Wool Festival, Squam Arts Workshops, the Taos Wool Festival, Sock Summit, and the Madrona Fiber Arts Winter Retreat.

Franklin’s varied experience in the fiber world includes contributions of writing and design to Vogue Knitting, Yarn Market News, Interweave Knits, Interweave Crochet, PieceWork, Twist Collective; and a regular columns and cartoons for Mason-Dixon Knitting, PLY Magazine, Lion Brand Yarns, and Skacel Collection/Makers’ Mercantile. Many of his independently published designs are available via Ravelry.com.

He is the longtime proprietor of The Panopticon, one of the most popular knitting blogs on the Internet (presently on hiatus).

Franklin lives in Chicago, Illinois, cohabiting shamelessly with 15,000 books, a Schacht spinning wheel, four looms, and a colony of yarn that multiplies whenever his back is turned.

Follow Franklin online via Twitter (@franklinhabit), Instagram (@franklin.habit), his Web site (franklinhabit.com) or his Facebook page.